|

To understand how the country got to this point of historic inequality, and why American middle class upward mobility seems to have stalled, you need to recall that period - when the roaring twenties came crashing down. The 1929 stock market crash and the Great Depression provoked a sea-change in U.S. government policies as it responded to a cataclysmic economic collapse. Jared Bernstein says the economic collapse of the 1930s ushered in a recognition that not only can markets fail, but that they can fail deeply and persistently.

"So a set of government institutions were set up to offset the worst market failures," he says. "Minimum wage, social security, unions, Medicare, Medicaid - all of these programs were built from a sensibility that said, markets are absolutely fundamental, but at the same time markets fail, and so government has a role to offset that."

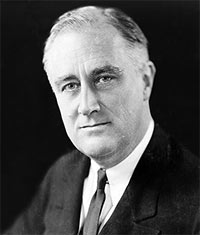

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Library of Congress |

|

It was, of course, Franklyn Roosevelt, who pushed this progressive view of government. And it was his New Deal policies - and the post-war economic boom -- that helped set the foundation for the growth of the modern American middle class. Matt Lassiter, a professor of history at the University of Michigan who has written about the rise of the middle class and the American suburbs, says the dream of being middle class and owning your own house had been around for a long time, but didn't become a widespread reality in the United States until after WW2.

"It's the depths of the great depression," Lassiter says, "and all of the mobility and instability of World War Two that created the conditions for government - more than any other actor - to say, we're going to do what it takes to make sure that people can have a decent home, that they can go to college, that they can get a decent job."

In his 1944 re-election campaign, Franklyn Roosevelt talked about what historians like Lassiter refer to as the new "social contract."

"[For the first time], it was the responsibility of government to make sure families had security," Lassiter explains, "that they had a home, decent health care, and especially that they had what everyone called at the time, "a decent standard of living."

Programs like the GI Bill to help veterans go to college and buy their own homes, the 1949 housing act to spur urban redevelopment, and a progressive tax code all helped build middle class upward mobility. So did FDR's push to give unions the right to organize, according to Peter Temin of M-I-T - who says all these policies helped make it possible for millions of Americans to latch on to a booming post-war economy.

"For the grand mass of people -- their incomes rose with productivity," Temin says. "So they were able to buy houses. They were able to buy cars. They were able to take vacations -- all the things that we think of as the basis for modern middle class life."

And one of the dominant story lines of post war America was the booming growth of the middle class.

"This was truly, in JFK's famous words, a rising tide lifted all boats," Temin says.

But Temin and Lassiter warn against an excessive sense of nostalgia about this period. While it was true that new economic opportunities were made available to a new middle class, there were racial and gender barriers that limited those opportunities.

"It was almost impossible for a female or a female-headed household to buy a home in the suburbs," says Lassiter. "And it was even more difficult for African Americans to live in white suburban developments. So we built a powerful middle class, but we also had these racial and gender divisions as well."

Even so, Jacob Hacker, an economist at the University of California at Berkeley and the author of the THE GREAT RISK SHIFT, says that post-war period of middle class growth represented a pivotal time of mass upward mobility. It was also a time shaped by a national consensus that accepted the notion that there are certain risks from abroad and at home that citizens need to share in common. It was a consensus that said, "We are in this together."

"And that consensus was so broadly felt that even Richard Nixon pushed for national health insurance," according to Hacker, who says, "that consensus broke down in the 1970s."

By then, the nation was in recession, plagued by double digit inflation with growing concerns about high taxes and excessive government regulation. So by the time Ronald Reagan came to power in 1980, a very different message was being pushed. It was Reagan, after all, who famously declared that "government is not the solution to our problems. Government is the problem." And according to Hacker, that message forged a new consensus that allowed these arguments to take root and grow.

"So we've faced 25 years of very harsh rhetoric," Hacker says, "about the role of government in helping to provide economic security."

For most of the past 25 years, the economy has continued to expand. But middle class wages have grown much more slowly. They essentially decoupled from the nation's economic growth. It's a change that coincided with a long period that redefined that contract between government and the people. From the New Deal and the Great Society, to the era of personal responsibility - when the government redefined "welfare," rejected national health care, and tried to scale back social security in favor of personal savings accounts. Elizabeth Warren, a professor at the Harvard Law School, and an expert on bankruptcy and the middle class economy, says the post-war period was a time when most of the laws and policies were designed to strengthen the middle class. They supported education, established an FHA to help people afford homes, they established a robust system of unemployment insurance. But in the 1980s, she says, the policies shifted.

"We turned the middle class from being the object of protection to being the profit center," Warren says,"something to be devoured. This is who you want to go after."

At his nominating convention in Denver this past summer, Barak Obama seemed to signal a shift in this long-running debate about the role of government in people's lives. If Ronald Reagan said government is the problem, Obama seemed to declare that there's too little government in people's lives. He took Republicans - and Democrats - to task for promoting the so called "ownership society." Obama said it smacked of "trickle down econcomics," and declared that what the "ownership society" really means is, "you're on your own." To Jacob Hacker of Berkeley it was the most explicit acknowledgement that the conservative critique of government, and the idea that we need to assume more responsibility, is out of step with the realities of the 21st Century. But Hacker says the challenge for the new President - and the country -- is to articulate precisely what the new role of government should be. Programs like Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid helped build a foundation of middle class security in the last century - but he says such programs need to be updated today.

"They're premised on the idea that families are always going to be a secure foundation because one of the parents will stay home - and that's no longer true," Hacker says. Hacker says many of these programs, which provide a means toward economic equality in the good times, and a safety net during the bad times, are based on the idea that people will work for a long time with a single employer who provides a generous pension and benefit. But he says all those assumptions no longer reflect the current reality.

"But because the debate has been so focused on the evils of government," Hacker says, "we haven't addressed that larger question: how do we create a 21st Century framework of economic security to reach for the American dream."

|

|